For the last 44 years, Bonnie Lucas has lived and worked in her one-bedroom walkup in SoHo, where the bathtub is, in fact, in the kitchen. (Lucas’ tub is painted a soft pink that matches her floors.) It’s here where the 73-year-old artist makes all her work, which are primarily collages made from thousands of items from 99-cent and discount stores — Disney princess ribbons, tiny pink plastic combs, little dolls — that she refigures into dense compositions that exalt and confound ideas of girlhood.

“When I grew up, to buy a doll and to take it apart was considered being a bad girl,” Lucas tells NYLON. “Purchased objects were meant to be used, looked at, valued. I feel like a sort of a naughty girl with my scissors and pliers ... It's so much fun to do the opposite of what you're told you can and can't do.”

Though her numerous shows around the world have received attention from critics, Lucas has been overlooked by collectors, museums, and larger art-world institutions. But in the past few years, a new generation is discovering her work during the revamped cultural obsession with girlhood. ILY2 Gallery in Portland, Oregon showed a retrospective of Lucas’ work in May. Now, she is showing at Eric Ruschman Gallery in Chicago, as well as New York City’s Trotter&Sholer, where, earlier this month, Lucas opened her solo show Small Worlds, which runs through March 2.

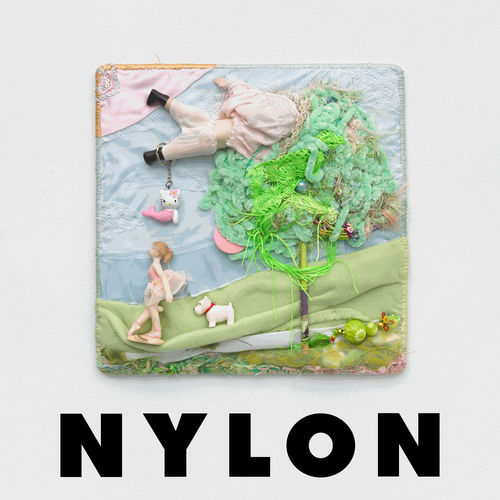

Though Lucas’ collages are small-scale objects of delicate beauty, they demand a deeper look, where they evoke an unsettling eeriness and tiny, hypnotic narratives unfold. In many of Lucas’ works, girls have lost their limbs; sometimes they have flowers for heads and branches for arms. Many of them are trapped, tied up, or upside down. Other times their dresses are raised a bit. “Life is dark,” Lucas says. “My art and the best art, I feel, has to reflect the complexities of real life.”

But there’s also an optimistic undercurrent, because for all the disfigured girls, there are just as many intact ones. They ride bicycles, cloaked in dresses and surrounded by flowers, or hold hands while walking through green fields. “I break a lot of rules about girlhood: cutting things up, taking heads off dolls, creating characters with feminine attributes that aren't sweet, that are in trouble, that lack limbs, that are buried,” Lucas says. “With all the obstacles, with all the things that didn't go well or that I had to struggle with, I'm still able to be creative. I think it's very hopeful work.”